Draw a 1000 Foot Circle Around 1869 S Bruck Street

Islamic geometric patterns are 1 of the major forms of Islamic ornamentation, which tends to avoid using figurative images, every bit it is forbidden to create a representation of an important Islamic figure according to many holy scriptures.

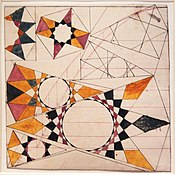

The geometric designs in Islamic art are often built on combinations of repeated squares and circles, which may be overlapped and interlaced, as tin arabesques (with which they are oftentimes combined), to course intricate and complex patterns, including a broad diverseness of tessellations. These may constitute the entire ornamentation, may form a framework for floral or calligraphic embellishments, or may retreat into the groundwork effectually other motifs. The complication and diversity of patterns used evolved from uncomplicated stars and lozenges in the ninth century, through a variety of 6- to thirteen-point patterns by the 13th century, and finally to include also 14- and 16-point stars in the sixteenth century.

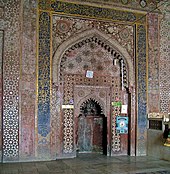

Geometric patterns occur in a diversity of forms in Islamic fine art and architecture. These include kilim carpets, Persian girih and Moroccan zellij tilework, muqarnas decorative vaulting, jali pierced stone screens, ceramics, leather, stained glass, woodwork, and metalwork.

Involvement in Islamic geometric patterns is increasing in the West, both amidst craftsmen and artists like Thousand. C. Escher in the twentieth century, and amid mathematicians and physicists such as Peter J. Lu and Paul Steinhardt.

Groundwork [edit]

Islamic decoration [edit]

Islamic art mostly avoids figurative images to avoid becoming objects of worship.[1] [two] This aniconism in Islamic civilisation acquired artists to explore non-figural art, and created a general aesthetic shift toward mathematically-based ornamentation.[3] The Islamic geometric patterns derived from simpler designs used in before cultures: Greek, Roman, and Sasanian. They are one of three forms of Islamic decoration, the others beingness the arabesque based on curving and branching found forms, and Islamic calligraphy; all iii are frequently used together.[4] [5]

Purpose [edit]

Authors such as Keith Critchlow[a] contend that Islamic patterns are created to pb the viewer to an agreement of the underlying reality, rather than being mere decoration, as writers interested just in design sometimes imply.[6] [7] In Islamic culture, the patterns are believed to be the bridge to the spiritual realm, the musical instrument to purify the heed and the soul.[8] David Wade[b] states that "Much of the fine art of Islam, whether in architecture, ceramics, textiles or books, is the art of decoration – which is to say, of transformation."[nine] Wade argues that the aim is to transfigure, turning mosques "into lightness and pattern", while "the decorated pages of a Qur'an tin become windows onto the space."[9] Against this, Doris Behrens-Abouseif[c] states in her book Beauty in Arabic Civilization that a "major difference" between the philosophical thinking of Medieval Europe and the Islamic world is exactly that the concepts of the good and the beautiful are separated in Arabic civilization. She argues that beauty, whether in poesy or in the visual arts, was enjoyed "for its ain sake, without commitment to religious or moral criteria".[10]

- Styles of Islamic geometric ornamentation

-

A variety of vernacular decorative Islamic styles in Morocco: girih-similar wooden panels, zellij tilework, stucco calligraphy, and floral door panels

-

An archway in the Ottoman Green Mosque, Bursa, Turkey (1424), with girih 10-point stars and pentagons

Pattern formation [edit]

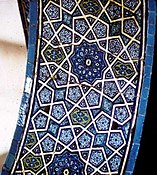

The Shah Nematollah Vali Shrine, Mahan, Iran, 1431. The blue girih-tiled dome contains stars with, from the top, 5, 7, ix, 12, 11, ix and x points in plow. 11-point stars are rare in Islamic art.[11]

Many Islamic designs are congenital on squares and circles, typically repeated, overlapped and interlaced to grade intricate and circuitous patterns.[4] A recurring motif is the 8-pointed star, often seen in Islamic tilework; it is made of two squares, one rotated 45 degrees with respect to the other. The 4th basic shape is the polygon, including pentagons and octagons. All of these tin be combined and reworked to class complicated patterns with a variety of symmetries including reflections and rotations. Such patterns can exist seen equally mathematical tessellations, which can extend indefinitely and thus suggest infinity.[four] [12] They are constructed on grids that require only ruler and compass to draw.[13] Artist and educator Roman Verostko argues that such constructions are in effect algorithms, making Islamic geometric patterns forerunners of modern algorithmic art.[fourteen]

The circle symbolizes unity and diverseness in nature, and many Islamic patterns are drawn starting with a circle.[xv] For instance, the ornamentation of the 15th-century mosque in Yazd, Persia is based on a circle, divided into six by vi circles drawn effectually it, all touching at its centre and each touching its two neighbours' centres to form a regular hexagon. On this basis is constructed a six-pointed star surrounded by vi smaller irregular hexagons to form a tessellating star pattern. This forms the basic design which is outlined in white on the wall of the mosque. That design, notwithstanding, is overlaid with an intersecting tracery in bluish effectually tiles of other colours, forming an elaborate pattern that partially conceals the original and underlying design.[xv] [16] A similar design forms the logo of the Mohammed Ali Inquiry Center.[17]

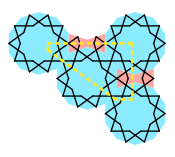

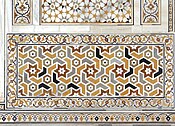

One of the early Western students of Islamic patterns, Ernest Hanbury Hankin, defined a "geometrical arabesque" equally a pattern formed "with the help of construction lines consisting of polygons in contact."[5] He observed that many different combinations of polygons tin be used as long equally the residual spaces between the polygons are reasonably symmetrical. For instance, a grid of octagons in contact has squares (of the same side as the octagons) every bit the balance spaces. Every octagon is the footing for an 8-point star, as seen at Akbar'due south tomb, Sikandra (1605–1613). Hankin considered the "skill of the Arabian artists in discovering suitable combinations of polygons .. near astounding."[5] He farther records that if a star occurs in a corner, exactly 1 quarter of it should be shown; if along an border, exactly one half of information technology.[v]

The Topkapı Curl, made in Timurid dynasty Iran in the late-15th century or beginning of the 16th century, contains 114 patterns including coloured designs for girih tilings and muqarnas quarter or semidomes.[eighteen] [19] [20]

The mathematical properties of the decorative tile and stucco patterns of the Alhambra palace in Granada, Kingdom of spain accept been extensively studied. Some authors have claimed on dubious grounds to have found most or all of the 17 wallpaper groups at that place.[21] [22] Moroccan geometric woodwork from the 14th to 19th centuries makes use of only v wallpaper groups, mainly p4mm and c2mm, with p6mm and p2mm occasionally and p4gm rarely; information technology is claimed that the "Hasba" (measure) method of construction, which starts with n-fold rosettes, can however generate all 17 groups.[23]

- Methods of construction

-

Construction of girih pattern in Darb-e Imam spandrel (xanthous line). Structure decagons bluish, bowties scarlet. The strapwork cuts across the construction tessellation.

-

Decoration in Tomb of I'timād-ud-Daulah, Agra, showing correct treatment of sides and corners. A quarter of each 6-point star is shown in each corner; one-half stars along the sides.

-

Architectural drawing for brick vaulting, Iran, probably Tehran, 1800–70

Development [edit]

Early on stage [edit]

The earliest geometrical forms in Islamic art were occasional isolated geometric shapes such as viii-pointed stars and lozenges containing squares. These engagement from 836 in the Great Mosque of Kairouan, Tunisia, and since then accept spread all across the Islamic world.[24]

Centre stage [edit]

The next development, marking the middle stage of Islamic geometric pattern usage, was of vi- and 8-point stars, which appear in 879 at the Ibn Tulun Mosque, Cairo, so became widespread.[24]

A wider diverseness of patterns were used from the 11th century. Abstract 6- and 8-signal shapes appear in the Tower of Kharaqan at Qazvin, Persia in 1067, and the Al-Juyushi Mosque, Egypt in 1085, once again becoming widespread from there, though vi-indicate patterns are rare in Turkey.[24]

In 1086, 7- and 10-point girih patterns (with heptagons, v- and 6-pointed stars, triangles and irregular hexagons) appear in the Jameh Mosque of Isfahan. 10-point girih became widespread in the Islamic globe, except in the Spanish Al-Andalus.[24] Before long afterwards, sweeping ix-, eleven-, and 13-bespeak girih patterns were used in the Barsian Mosque, likewise in Persia, in 1098; these, like 7-signal geometrical patterns, are rarely used outside Persia and central Asia.[24]

Finally, marking the end of the heart stage, 8- and 12-point girih rosette patterns announced in the Alâeddin Mosque at Konya, Turkey in 1220, and in the Abbasid palace in Baghdad in 1230, going on to get widespread across the Islamic world.[24]

Late stage [edit]

The beginning of the late phase is marked by the apply of simple 16-point patterns at the Hasan Sadaqah mausoleum in Cairo in 1321, and in the Alhambra in Spain in 1338–1390. These patterns are rarely found outside these two regions. More than elaborate combined 16-point geometrical patterns are found in the Sultan Hassan complex in Cairo in 1363, but rarely elsewhere. Finally, 14-point patterns appear in the Jama Masjid at Fatehpur Sikri in India in 1571–1596, just in few other places.[24] [d]

Artforms [edit]

Several artforms in different parts of the Islamic world brand utilize of geometric patterns. These include ceramics,[26] girih strapwork,[27] jali pierced stone screens,[28] kilim rugs,[29] leather,[30] metalwork,[31] muqarnas vaulting,[32] shakaba stained drinking glass,[33] woodwork,[27] and zellij tiling.[34]

Ceramics [edit]

Ceramics lend themselves to circular motifs, whether radial or tangential. Bowls or plates tin can be decorated inside or out with radial stripes; these may be partly figurative, representing stylised leaves or bloom petals, while circular bands can run around a bowl or jug. Patterns of these types were employed on Islamic ceramics from the Ayyubid period, 13th century. Radially symmetric flowers with, say, six petals lend themselves to increasingly stylised geometric designs which can combine geometric simplicity with recognisably naturalistic motifs, brightly coloured glazes, and a radial composition that ideally suits circular crockery. Potters oftentimes chose patterns suited to the shape of the vessel they were making.[26] Thus an unglazed earthenware h2o flask[due east] from Aleppo in the shape of a vertical circle (with handles and neck above) is decorated with a band of moulded braiding around an Arabic inscription with a modest viii-petalled blossom at the heart.[35]

Girih tilings and woodwork [edit]

Girih are elaborate interlacing patterns formed of five standardized shapes. The fashion is used in Persian Islamic architecture and also in decorative woodwork.[27] Girih designs are traditionally made in unlike media including cut brickwork, stucco, and mosaic faience tilework. In woodwork, especially in the Safavid period, it could exist practical either as lattice frames, left plain or inset with panels such as of coloured glass; or every bit mosaic panels used to decorate walls and ceilings, whether sacred or secular. In compages, girih forms decorative interlaced strapwork surfaces from the 15th century to the 20th century. Nigh designs are based on a partially hidden geometric grid which provides a regular array of points; this is made into a pattern using 2-, 3-, 4-, and half-dozen-fold rotational symmetries which tin can fill the airplane. The visible pattern superimposed on the grid is also geometric, with vi-, viii-, 10- and 12-pointed stars and a diversity of convex polygons, joined by straps which typically seem to weave over and under each other.[27] [36] The visible pattern does non coincide with the underlying structure lines of the tiling.[27] The visible patterns and the underlying tiling represent a bridge linking the invisible to the visible, coordinating to the "epistemological quest" in Islamic culture, the search for the nature of knowledge.[37]

Jali [edit]

Mosque of Ibn Tulun: window with girih-style 10-indicate stars (at rear), with floral roundels in octagons forming a frieze at front

Jali are pierced stone screens with regularly repeating patterns. They are feature of Indo-Islamic architecture, for example in the Mughal dynasty buildings at Fatehpur Sikri and the Taj Mahal. The geometric designs combine polygons such as octagons and pentagons with other shapes such as 5- and 8-pointed stars. The patterns emphasized symmetries and suggested infinity by repetition. Jali functioned equally windows or room dividers, providing privacy merely allowing in air and calorie-free.[28] Jali forms a prominent element of the compages of India.[38] The use of perforated walls has declined with modern edifice standards and the need for security. Modern, simplified jali walls, for example made with pre-moulded clay or cement blocks, have been popularised past the architect Laurie Bakery.[39] Pierced windows in girih way are sometimes found elsewhere in the Islamic world, such equally in windows of the Mosque of Ibn Tulun in Cairo.[40]

Kilim [edit]

Somewhat geometric motifs such as the Wolf'due south Mouth (Kurt Aǧzi), to protect the flocks confronting wolves, are oft woven into tribal kilims.

A kilim is an Islamic[29] flatwoven carpet (without a pile), whether for household use or a prayer mat. The design is made past winding the weft threads back over the warp threads when a colour purlieus is reached. This technique leaves a gap or vertical slit, so kilims are sometimes called slit-woven textiles. Kilims are oft decorated with geometric patterns with 2- or 4-fold mirror or rotational symmetries. Considering weaving uses vertical and horizontal threads, curves are difficult to generate, and patterns are appropriately formed mainly with direct edges.[16] [41] Kilim patterns are oft feature of specific regions.[42] Kilim motifs are often symbolic likewise equally decorative. For case, the wolf'southward mouth or wolf's human foot motif (Turkish: Kurt Aǧzi, Kurt İzi) expresses the tribal weavers' desires for protection of their families' flocks from wolves.[43]

Leather [edit]

Islamic leather is often embossed with patterns similar to those already described. Leather book covers, starting with the Quran where figurative artwork was excluded, were decorated with a combination of kufic script, medallions and geometric patterns, typically bordered by geometric braiding.[30]

Metalwork [edit]

Metal artefacts share the aforementioned geometric designs that are used in other forms of Islamic fine art. However, in the view of Hamilton Gibb, the accent differs: geometric patterns tend to be used for borders, and if they are in the main decorative area they are virtually oftentimes used in combination with other motifs such as floral designs, arabesques, animate being motifs, or calligraphic script. Geometric designs in Islamic metalwork can form a filigree decorated with these other motifs, or they tin can class the groundwork pattern.[31]

Even where metallic objects such equally bowls and dishes practise not seem to have geometric decoration, still the designs, such every bit arabesques, are often ready in octagonal compartments or arranged in concentric bands around the object. Both closed designs (which practise not echo) and open up or repetitive patterns are used. Patterns such as interlaced 6-pointed stars were especially pop from the 12th century. Eva Baer[f] notes that while this design was essentially simple, it was elaborated by metalworkers into intricate patterns interlaced with arabesques, sometimes organised around further basic Islamic patterns, such as the hexagonal pattern of half dozen overlapping circles.[45]

Muqarnas [edit]

Muqarnas are elaborately carved ceilings to semi-domes, oft used in mosques. They are typically made of stucco (and thus do non take a structural function), but can also be of forest, brick, and stone. They are characteristic of Islamic compages of the Heart Ages from Spain and Kingdom of morocco in the west to Persia in the e. Architecturally they form multiple tiers of squinches, diminishing in size as they rise. They are often elaborately decorated.[32]

Stained glass [edit]

Geometrically patterned stained glass is used in a variety of settings in Islamic architecture. It is plant in the surviving summertime residence of the Palace of Shaki Khans, Azerbaijan, constructed in 1797. Patterns in the "shabaka" windows include half-dozen-, eight-, and 12-betoken stars. These wood-framed decorative windows are distinctive features of the palace's architecture. Shabaka are however constructed the traditional way in Sheki in the 21st century.[33] [46] Traditions of stained glass set in wooden frames (not atomic number 82 as in Europe) survive in workshops in Iran as well as Azerbaijan.[47] Glazed windows set up in stucco arranged in girih-similar patterns are found both in Turkey and the Arab lands; a late example, without the traditional remainder of design elements, was made in Tunisia for the International Colonial Exhibition in Amsterdam in 1883.[48] The old metropolis of Sana'a in Republic of yemen has stained glass windows in its tall buildings.[49]

Zellij [edit]

Zellij (Arabic: الزَّلِيْج) is geometric tilework with glazed terracotta tiles set into plaster, forming colourful mosaic patterns including regular and semiregular tessellations. The tradition is characteristic of Morocco, but is also found in Moorish Spain. Zellij is used to decorate mosques, public buildings and wealthy private houses.[34]

Illustrations [edit]

- Media used for Islamic geometric patterns

-

Safavid bowl with radial and circular motifs, Persia, 17th century

-

Lustre tiles from Iran, probably Kashan, 1262, in the shapes of the Sufi symbols for the divine jiff

-

-

Woven wool Kilim from Turkey

-

Leather prayer book cover, Persia, 16th century

-

Exterior Islamic art [edit]

In Western civilization [edit]

It is sometimes supposed in Western social club that mistakes in repetitive Islamic patterns such as those on carpets were intentionally introduced equally a evidence of humility past artists who believed only Allah tin produce perfection, merely this theory is denied.[51] [52] [53]

Major Western collections hold many objects of widely varying materials with Islamic geometric patterns. The Victoria and Albert Museum in London holds at least 283 such objects, of materials including wallpaper, carved wood, inlaid wood, can- or pb-glazed earthenware, contumely, stucco, drinking glass, woven silk, ivory, and pen or pencil drawings.[54] The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York has amidst other relevant holdings 124 mediaeval (grand–1400 A.D.) objects bearing Islamic geometric patterns,[55] including a pair of Egyptian minbar (pulpit) doors almost ii m. high in rosewood and mulberry inlaid with ivory and ebony;[56] and an entire mihrab (prayer niche) from Isfahan, busy with polychrome mosaic, and weighing over 2,000 kg.[57]

Wooden box inlaid with ivory with zellij-similar geometrical motifs. Italian republic (Florence or Venice) 15th century.

Islamic decoration and craftsmanship had a meaning influence on Western fine art when Venetian merchants brought goods of many types dorsum to Italia from the 14th century onwards.[58]

The Dutch artist M. C. Escher was inspired by the Alhambra's intricate decorative designs to study the mathematics of tessellation, transforming his style and influencing the rest of his creative career.[59] [threescore] In his own words it was "the richest source of inspiration I have ever tapped."[61]

Influence on the sciences [edit]

Cultural organisations such every bit the Mathematical Sciences Research Institute and the Institute for Advanced Written report run events on geometric patterns and related aspects of Islamic art.[62] In 2013 the Istanbul Center of Design and the Ensar Foundation ran what they claimed was the kickoff e'er symposium of Islamic Arts and Geometric Patterns, in Istanbul. The console included the experts on Islamic geometric pattern Carol Bier,[g] Jay Bonner,[h] [65] Eric Broug,[i] Hacali Necefoğlu[j] and Reza Sarhangi.[thousand] [69] In Britain, The Prince's School of Traditional Arts runs a range of courses in Islamic fine art including geometry, calligraphy, and arabesque (vegetal forms), tile-making, and plaster etching.[70]

Tomb towers of ii Seljuk princes at Kharaghan, Qazvin province, Iran, covered with many unlike brick patterns like those that inspired Ahmad Rafsanjani to create auxetic materials

Computer graphics and computer-aided manufacturing go far possible to design and produce Islamic geometric patterns finer and economically. Craig S. Kaplan explains and illustrates in his Ph.D. thesis how Islamic star patterns can be generated algorithmically.[71]

Two physicists, Peter J. Lu and Paul Steinhardt, attracted controversy in 2007 by claiming[72] that girih designs such as that used on the Darb-e Imam shrine[l] in Isfahan were able to create quasi-periodic tilings resembling those discovered past Roger Penrose in 1973. They showed that rather than the traditional ruler and compass construction, it was possible to create girih designs using a set of 5 "girih tiles", all equilateral polygons, secondarily decorated with lines (for the strapwork).[73]

In 2016, Ahmad Rafsanjani described the use of Islamic geometric patterns from tomb towers in Iran to create auxetic materials from perforated prophylactic sheets. These are stable in either a contracted or an expanded state, and can switch between the two, which might be useful for surgical stents or for spacecraft components. When a conventional fabric is stretched along 1 axis, it contracts along other axes (at right angles to the stretch). Simply auxetic materials expand at right angles to the pull. The internal structure that enables this unusual behaviour is inspired by 2 of the lxx Islamic patterns that Rafsanjani noted on the tomb towers.[74]

Notes [edit]

- ^ Critchlow is a professor of compages, and the writer of a volume on Islamic patterns.

- ^ Wade is the writer of a series of books on pattern in various artforms.

- ^ Behrens-Abouseif is a professor of the history of art and architecture at SOAS.

- ^ One such place is the Mustansiriyya Madrasa in Baghdad, every bit illustrated by Broug.[25]

- ^ Leaving the flask porous allowed evaporation, keeping the water cool.[35]

- ^ Baer is Emeritus Professor of Islamic Studies at Tel Aviv University.[44]

- ^ Bier is a historian of Islamic art who studies blueprint.[63]

- ^ Bonner is an architect specialising in Islamic ornament.[64]

- ^ Broug writes books and runs courses on Islamic geometric design.[66]

- ^ Necefoğlu is a professor of chemistry at Kafkas University interested in design and crystallography.[67]

- ^ Sarhangi is the founder of The Bridges Organization. He studies the mathematics of Western farsi architecture and mosaic design.[68]

- ^ Illustrated above.

References [edit]

- ^ Bouaissa, Malikka (27 July 2013). "The crucial role of geometry in Islamic art". Al Arte Magazine. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ^ Bonner, Jay (2017). Islamic geometric patterns : their historical evolution and traditional methods of construction. New York: Springer. p. 1. ISBN978-1-4419-0216-0. OCLC 1001744138.

- ^ Bier, Ballad (Sep 2008). "Fine art and Mithãl: Reading Geometry as Visual Commentary". Iranian Studies. 41: 9. doi:10.1080/00210860802246176. JSTOR 25597484. S2CID 171003353.

- ^ a b c "Geometric Patterns in Islamic Art". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ^ a b c d Hankin, Ernest Hanbury (1925). The Drawing of Geometric Patterns in Saracenic Art. Memoirs of the Archaeological Survey of India No. 15. Government of Republic of india Central Publication Branch.

- ^ Critchlow, Keith (1976). Islamic Patterns : an belittling and cosmological approach. Thames and Hudson. ISBN0-500-27071-half dozen.

- ^ Field, Robert (1998). Geometric Patterns from Islamic Fine art & Compages. Tarquin Publications. ISBN978-1-899618-22-iv.

- ^ Ahuja, Mangho; Loeb, A. Fifty. (1995). "Tessellations in Islamic Calligraphy". Leonardo. 28 (1): 41–45. doi:10.2307/1576154. JSTOR 1576154. S2CID 191368443.

- ^ a b Wade, David. "The Evolution of Style". Pattern in Islamic Art . Retrieved 12 April 2016.

Much of the art of Islam, whether in architecture, ceramics, textiles or books, is the fine art of decoration – which is to say, of transformation. The aim, however, is never merely to ornament, just rather to transfigure. ... The vast edifices of mosques are transformed into lightness and pattern; the decorated pages of a Qur'an can get windows onto the infinite. Maybe most chiefly, the Word, expressed in countless calligraphic variations, e'er conveys the impression that it is more indelible than the objects on which information technology is inscribed.

- ^ Behrens-Abouseif, Doris (1999). Beauty in Arabic Culture. Markus Wiener. pp. 7–8. ISBN978-1-558-76199-five.

- ^ Broug, Eric (2008). Islamic Geometric Patterns. Thames and Hudson. pp. 183–185, 193. ISBN978-0-500-28721-7.

- ^ Hussain, Zarah (30 June 2009). "Introduction to Islamic fine art". BBC. Retrieved 1 Dec 2015.

- ^ Bellos, Alex; Broug (Illustrator), Eric (x February 2015). "Muslim rule and compass: the magic of Islamic geometric design". The Guardian . Retrieved i Dec 2015.

- ^ Verostko, Roman (1999) [1994]. "Algorithmic Art".

- ^ a b Henry, Richard. "Geometry – The Language of Symmetry in Islamic Fine art". Art of Islamic Pattern . Retrieved 1 Dec 2015.

- ^ a b Lockerbie, John. "Islamic Pattern: Arabic / Islamic geometry 01". Catnaps.org. Archived from the original on 13 Apr 2019. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ^ "Islamic Fine art and Geometric Pattern". MOHA. 2014. Archived from the original on 3 December 2015. Retrieved iii December 2015. The logo's construction is demonstrated in an animation on the MOHA website.

- ^ Gülru Necipoğlu (1992). Geometric Pattern in Timurid/Turkmen Architectural Practice: Thoughts on a Recently Discovered Coil and Its Late Gothic Parallels (PDF). Timurid Art and Culture – Islamic republic of iran and Cardinal Asia in the Fifteenth Century (eds (Golombek, 50. and Subtelny, One thousand.). East.J. Brill.

- ^ Saliba, George (1999). "Artisans and Mathematicians in Medieval Islam. The Topkapi Whorl: Geometry and Decoration in Islamic Architecture by Gülru Necipoğlu (Review)". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 119 (4): 637–645. doi:10.2307/604839. JSTOR 604839. (subscription required)

- ^ van den Hoeven, Saskia, van der Veen, Maartje. "Muqarnas-Mathematics in Islamic Arts" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 15 January 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Perez-Gomez, R. (1987). "The Iv Regular Mosaics Missing in the Alhambra" (PDF). Comput. Math. Applic. xiv (2): 133–137. doi:ten.1016/0898-1221(87)90143-x.

- ^ Grünbaum, Branko (June 2006). "What Symmetry Groups Are Present in the Alhambra?" (PDF). Notices of the AMS. 53 (half-dozen): 670–673.

- ^ Aboufadil, Y.; Thalal, A.; Raghni, M. A. Eastward. I. (2013). "Symmetry groups of Moroccan geometric woodwork patterns". Periodical of Applied Crystallography. 46 (6): 1834–1841. doi:10.1107/S0021889813027726.

- ^ a b c d e f g Abdullahi, Yahya; Bin Embi, Mohamed Rashid (2013). "Development of Islamic geometric patterns". Frontiers of Architectural Research. 2 (two): 243–251. doi:10.1016/j.foar.2013.03.002.

- ^ Broug, Eric (2013). Islamic Geometric Blueprint. Thames and Hudson. p. 173. ISBN978-0-500-51695-9.

- ^ a b "Geometric Ornamentation and the Fine art of the Book. Ceramics". Museum with no Frontiers. Retrieved 7 December 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Gereh-Sāzī. Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved two December 2015.

- ^ a b "For Educators: Geometric Design in Islamic Fine art: Image 15". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ^ a b Thompson, Muhammad; Begum, Nasima. "Islamic Textile Art and how it is Misunderstood in the West – Our Personal Views". Salon du Tapis d'Orient. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- ^ a b "Geometric Decoration and the Art of the Book. Leather". Museum with no Frontiers. Retrieved seven Dec 2015.

- ^ a b Gibb, Sir Hamilton Alexander Rosskeen (1954). The Encyclopaedia of Islam. Brill Annal. pp. 990–992. GGKEY:N71HHP1UY5E.

- ^ a b Tabbaa, Yasser. "The Muqarnas Dome: Its Origin and Significant" (PDF). Archnet. pp. 61–74. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 December 2015. Retrieved two December 2015.

- ^ a b Male monarch, David C. King (2006). Azerbaijan . Marshall Cavendish. p. 99. ISBN978-0-7614-2011-viii.

- ^ a b Njoku, Raphael Chijioke (2006). Culture and Community of Kingdom of morocco. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 58. ISBN978-0-313-33289-0.

- ^ a b "Flask". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 7 December 2015.

- ^ "Gereh-Sazi". Tebyan. xx Baronial 2011. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- ^ Hooman, Koliji (April 2016). "Gazing Geometries: Modes of Design Thinking in Pre-Modern Cardinal Asia and Persian Architecture". Nexus Network Journal. 18: 105–132. doi:10.1007/s00004-016-0288-half dozen.

- ^ "intypes. perforate". Cornell University. Retrieved 18 Jan 2016.

- ^ Varanashi, Satyaprakash (30 January 2011). "The multi-functional jaali". The Hindu . Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- ^ Mozzati, Luca (2010). Islamic Art. Prestel. p. 27. ISBN978-3-7913-4455-3.

- ^ "CARPETS five. Apartment-woven carpets: Techniques and structures". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- ^ "Turkish Kilim Carpeting". Through the Collector's Eye . Retrieved 3 Dec 2015.

- ^ Erbek, Güran (1998). Kilim Catalogue No. 1. May Selçuk A. S. Edition=1st.

- ^ Baer, Eva (1989). Ayyubid Metalwork With Christian Images. ISBN9004089624 . Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- ^ Baer, Eva (1983). Metalwork in Medieval Islamic Art. SUNY Press. pp. 122–132. ISBN978-0-87395-602-four.

- ^ Sharifov, Azad (1998). "Shaki Paradise in the Caucasus Foothills". Azerbaijan International. 6 (2): 28–35.

- ^ Alin, Marina (21 January 2014). "Wood, glass, geometry – stained glass in Islamic republic of iran and Azerbaijan". Islamic Arts & Architecture. Archived from the original on 26 January 2016. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- ^ "Carved stucco and stained glass window". Islamic Arts & Architecture. 16 December 2011. Archived from the original on 26 Jan 2016. Retrieved eighteen Jan 2016.

- ^ Hansen, Eri c (21 December 2011). "Sana'a Rising – "a Venice built on sand."". Islamic Arts & Architecture. Archived from the original on 26 Jan 2016. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- ^ Locher, J. Fifty. (1971). The World of Chiliad. C. Escher. Abrams. p. 17. ISBN0-451-79961-5.

- ^ Thompson, Muhammad; Begum, Nasima. "Islamic Fabric Art: Anomalies in Kilims". Salon du Tapis d'Orient. TurkoTek. Retrieved 25 August 2009.

- ^ Alexenberg, Melvin 50. (2006). The hereafter of art in a digital age: from Hellenistic to Hebraic consciousness . Intellect. p. 55. ISBN1-84150-136-0.

- ^ Backhouse, Tim. "Only God is Perfect". Islamic and Geometric Fine art . Retrieved 25 August 2009.

- ^ "Search the Collections "Islamic geometric blueprint"". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ^ "Islamic geometric pattern A.D. 1000–1400". Metropolitan Museum of Fine art. Retrieved ii December 2015.

- ^ "Pair of Minbar Doors". Metropolitan Museum of Fine art. Retrieved 2 Dec 2015.

- ^ "Mihrab (Prayer Niche)". Metropolitan Museum of Fine art. Retrieved 2 Dec 2015.

- ^ Mack, Rosamond E. (2001). Boutique to Piazza: Islamic Merchandise and Italian Art, 1300-1600. University of California Press. pp. Chapter 1. ISBN0-520-22131-ane.

- ^ Roza, Greg (2005). An Optical Artist: Exploring Patterns and Symmetry. Rosen Classroom. p. twenty. ISBN978-1-4042-5117-five.

- ^ Monroe, J. T. (2004). Hispano-Arabic Poetry: A Educatee Anthology. Gorgias Press LLC. p. 65. ISBN978-one-59333-115-iii.

- ^ O'Connor, J. J.; Robertson, E. F. (May 2000). "Maurits Cornelius Escher". Biographies. University of St Andrews. Retrieved two Nov 2015. which cites Strauss, Due south. (9 May 1996). "M C Escher". The Globe and Mail.

- ^ "Geometric Patterns in Islamic Art". National Math Festival. Archived from the original on eight December 2015. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- ^ "Selected Works of Carol Bier". SelectedWorks . Retrieved 3 Dec 2015.

- ^ Bonner, Jay. "About". Bonner Pattern. Retrieved iii Dec 2015.

- ^ Bonner, Jay (2017). Islamic geometric patterns : their historical evolution and traditional methods of construction. New York: Springer. ISBN978-1-4419-0216-0. OCLC 1001744138.

- ^ "School of Islamic Geometric Blueprint". Eric Broug. Retrieved 1 Dec 2015.

- ^ "Prof.Dr. Hacali Necefoğlu (Fen Edebiyat Fakültesi)". Akademik Bilgi Sistemi (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 5 May 2018. Retrieved 3 Dec 2015.

- ^ "Reza Sarhangi". Towson University. Archived from the original on 27 November 2015. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- ^ "Istanbul hosts beginning ever Islamic geometric arts symposium". World Bulletin. 25 September 2013. Retrieved iii December 2015.

- ^ "Introduction to Islamic Art". The Prince'southward School of Traditional Arts. Archived from the original on 3 Dec 2015. Retrieved four December 2015.

- ^ Kaplan, Craig S. (2002). "Computer Graphics and Geometric Ornamental Pattern: Chapter 3. Islamic Star Patterns". University of Waterloo (PhD thesis). Archived from the original on 30 December 2015. Retrieved 4 Dec 2015.

- ^ Lu, P. J.; Steinhardt, P. J. (2007). "Decagonal and Quasi-crystalline Tilings in Medieval Islamic Architecture". Scientific discipline. 315 (5815): 1106–1110. Bibcode:2007Sci...315.1106L. doi:10.1126/science.1135491. PMID 17322056. S2CID 10374218.

- ^ Ball, Philip (22 Feb 2007). "Islamic tiles reveal sophisticated maths". Nature: news070219–nine. doi:ten.1038/news070219-9. S2CID 178905751. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- ^ Webb, Jonathan (xvi March 2016). "Islamic art inspires stretchy, switchable materials". British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

External links [edit]

- Museum with no Frontiers: Geometric Ornament

- Victoria and Albert Museum: Teachers' resources: Maths and Islamic fine art & design

moraleshisday1968.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Islamic_geometric_patterns

0 Response to "Draw a 1000 Foot Circle Around 1869 S Bruck Street"

Post a Comment